Breathing (or respiration) is the most basic function of life and something we frequently take for granted… until it becomes difficult. Our respiratory systems manage stressors from the environment every minute of every day. These stressors can be particulates from dust and pollution, or microbes such as bacteria, viruses, and fungal spores. The respiratory immune system usually responds to these stressors by neutralising them with an active immune response and suspending them in mucous for clearance.

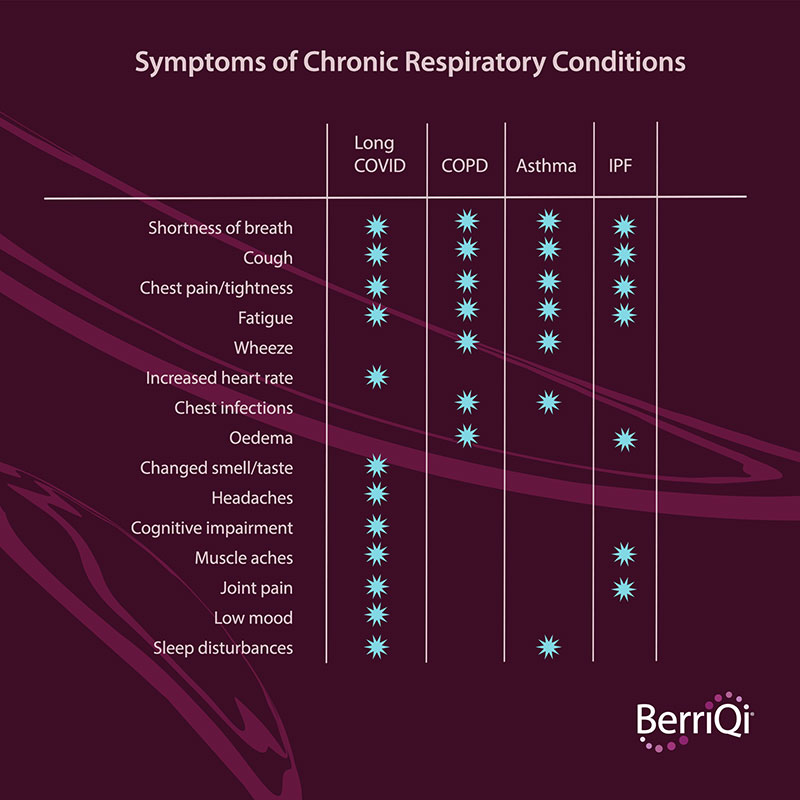

Most respiratory symptoms that people initially experience, such as coughing and wheezing, are characteristic of an initial immune response. Occasionally the immune system has a disproportionately major response to a relatively minor stressor. When the immune system enters that kind of overdrive, it cruises right through checkpoints meant to shut the response down after a stressor has been neutralised and cleared. This lack of immune regulation can lead to chronic conditions such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), or long-COVID. While the initial stressor is often quite different, the symptoms that people experience overlap due to generalised airway remodelling (Table 1).

Symptoms of chronic respiratory conditions

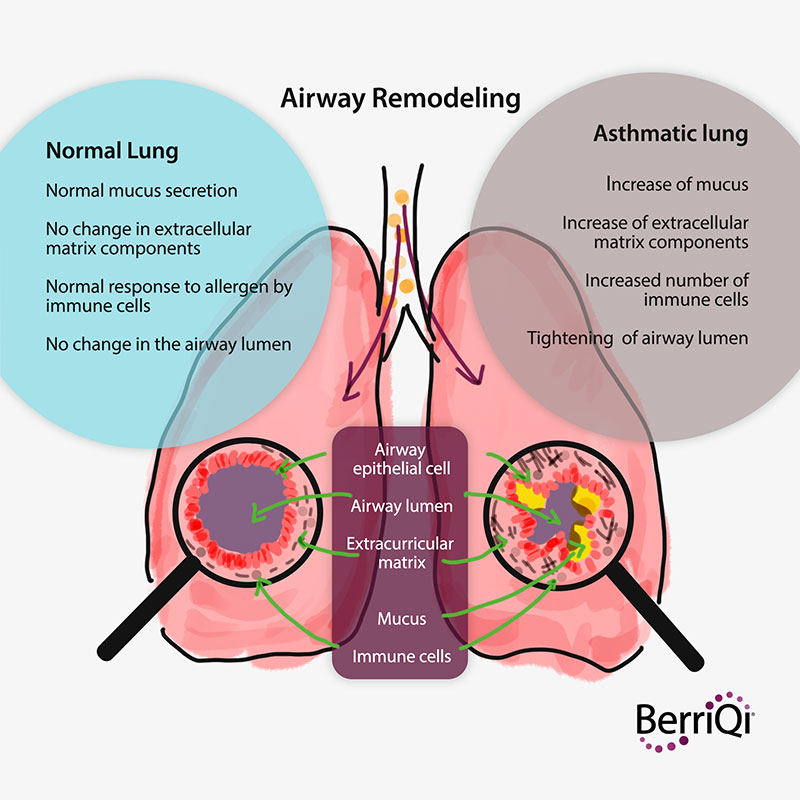

Airway remodelling refers to the structural changes that take place in both large and small airway structures during disease progression. Inflammation is a form of short-term airway remodelling that reduces lung capacity, but the resulting scar tissue poses serious chronic threats to respiratory health and quality of life. As scar tissue increases with disease progression, the stretchiness of the lungs decreases and gas transfer between the lungs and the blood stream is reduced.

Together this presents as shortness of breath as our bodies work to bring more oxygen into the blood stream. This shortness of breath may be noticed during everyday activities such as showering, bending down, walking, talking, eating, and exercise. People often cough in response to what feels like obstructions in the airways, which can perpetuate irritation in the airways and further stress the muscles in the diaphragm, torso, and throat. Chest discomfort and fatigue result from the combined increased exertion and low blood oxygen levels.

So now that we know what is going on in remodelled lungs and how we can diagnose it, how is it currently treated?

Treatments vary according to the type, origin and severity of the disease.

- Corticosteroids are immunosuppressive and may be beneficial in helping to control an overactive immune system. Similarly, anti-inflammatory agents such as methotrexate, colchicine and others may provide some relief and prevention prior to the establishment of scar tissue.

- Pirfenidone and nintedanib are anti-scarring agents which inhibit molecular pathways involved in the underlying wound healing and inflammatory pathways involved in fibrosis progression.

- Oxygen supplementation supplied through a tube called a cannula, or via a facemask, during sleep and exercise is a common non-invasive method to help boost blood oxygen levels. As the disease progresses, oxygen may be needed all the time. Supplying oxygen reduces shortness of breath and improves quality of life and exercise capacity.

- Lung transplantation may be required as a last resort for extension of life.

What is happening at the cellular level during airway remodelling? It is actually very complex, but there are a few commonalities: collagen fibre deposition and immune cell infiltration.

Collagen fibres are deposited by macrophages, or more often, fibroblasts and/or myofibroblasts. This is a wound-healing response, from injury, insult or inflammation. Irrespective of the cause of the damage and as a part of the response, collagen is deposited outside and in between the cells to structurally support the damaged area. Unfortunately, this can happen throughout the lungs. As these fibrous protein cables thicken into scars, the lung tissue loses its ability to stretch.

Immune cell infiltration. In many (but not all) cases of airway remodelling the tissues of the alveoli are infiltrated by various types of immune cells. The presence of these densely packed cells causes tissue swelling, further contributing to lung inflexibility and wall thickening. The serum from the blood leaks in through the areas where the immune cells were admitted from the blood vessels, causing additional swelling (turgor) and further adding to thickening and inflexibility.

Diagnosing airway remodelling from any cause is done by assessing the stretchiness/stiffness of lungs, blood oxygen levels, the sound of air moving through the airways, and sometimes scans.

- Stiff lungs are detected using breathing tests called spirometry which measures lung capacity.

- Blood oxygen is usually measured with a common non-invasive medical device such as a finger-clamp pulse oximeter, which measures how much light is absorbed by the haemoglobin in arterial blood circulating between the lights and sensors. Well oxygenated blood absorbs more infrared light while letting red light pass through. A 95% or higher SpO2 reading on a home pulse oximeter is healthy.

- Sound. Bring in the old school stethoscope. The sound of air moving through the lungs can tell a doctor a lot about whether there is inflammation causing a wheeze, or if there is stiffness of the alveoli causing a crackling sound called “rales”.

- Lung scans. Lung CT scans may reveal fibrous lung tissue, called ground glass opacity (GGO), named for its appearance that looks like frosting on a glass windowpane. This has been observed in the lungs of survivors of covid-19.